This Black History Month, a Sampling of African-American Historic Places in Southern Arizona

- Alesha Adolph

- Feb 26, 2022

- 9 min read

Dunbar Pavilion: In 1909, Arizona passed a law mandating that Arizona school children be segregated by race for their first 8 years of school. In 1912, when Arizona became a state, the wording changed from “mandatory” segregation to “permissible to segregate.” The Tucson School District decided to follow along and create a Colored School. The first classes were held in a vacant building at 215 E Sixth Street and taught by Mr. Cicero Simmons. African American families protested the segregation of their children by boycotting the school for two weeks. In 1917, the school moved to a larger location on West Second Street and became the Paul Laurence Dunbar School. Once the school opened it became a place for community activities. With the help from teachers and parents, the students managed to receive a good education. Before 1920, students graduating from Dunbar who wanted to continue their education were forced to teach each other in the old Roskruge School after the other students’ classes were done. In the 1920’s this changed, and students were allowed to attend Tucson High School. (The Dunbar Pavilion, n.d.) The Jr. High School was added in 1948. In 1951, Tucson schools agreed to dismantle the segregated school system. The Dunbar School was integrated in 1952. During the course of the thirty-eight years of the school's history it underwent three name changes. It was known as the "Colored School" in 1913, Dunbar Junior High in 1917, and after segregation of Arizona schools was ended in 1951, it was renamed John A. Spring. Today, it is referred to as the Dunbar Pavilion. The Jr. High school classrooms have been refinished and are being used by the IDEA School, The Visual and Textile Arts of Tucson Inc., and the Dunbar Barber Academy. For more information check out their website here.

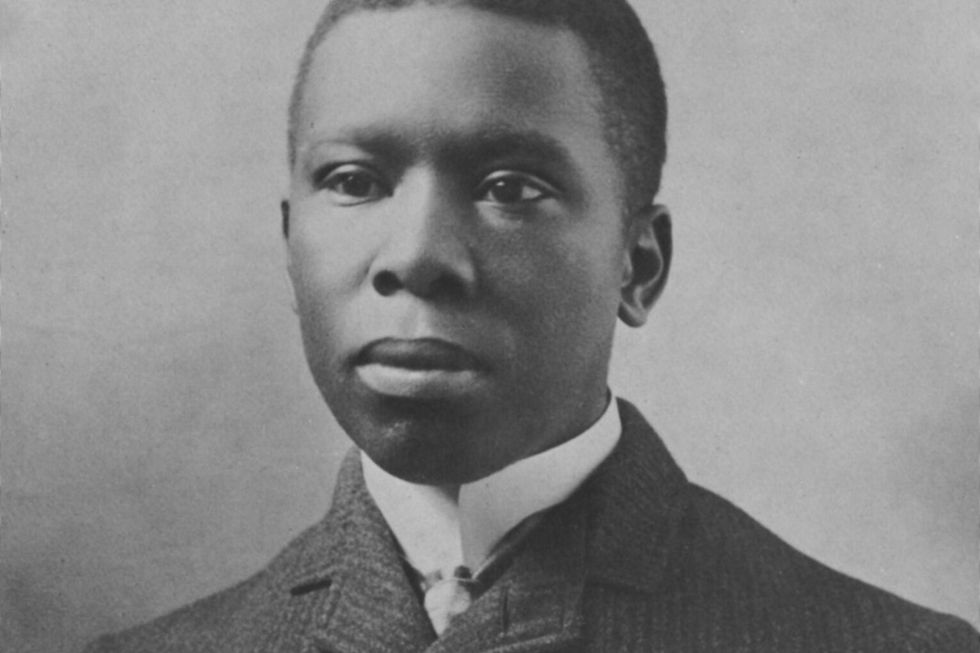

Paul Laurence Dunbar: Paul Laurence Dunbar was born on June 27, 1872, to parents Joshua and Matilda Murphy Dunbar who were formerly enslaved in Kentucky. He was one of the first African American poets to get recognition and became influential in American literature. He drew on stories from his parents and his own lives as inspiration for his work. While in high school he had poems published in the Dayton Herald and he edited the Dayton Tattler published by Orville Wright. He was the only African American in his class, and he became class president and class poet. In 1892, a former teacher invited him to read his poems at a Western Association of Writers meeting, which impressed the audience. In 1893, he self-published a collection called Oak and Ivy. The collection did well, and he decided to continue to pursue his literary career. Later that year he moved to Chicago and met Frederick Douglass who arranged for him to read a selection of poems. He made other friends along the way who helped him and promoted his work. Charles A. Thatcher and Henry A. Tobey helped Dunbar to publish his second collection Majors and Minors in 1895. They also helped him get an agent, book readings and a publishing contract which led him to publish his third collection Lyrics of a Lowly Life in 1896. This collection did well, and he went on a six-month tour of England. It helped to establish Dunbar as “the nation’s foremost Black poet” (Poetry Foundation, 2022). When he returned to America, he moved to Washington D.C. for a clerkship at the Library of Congress in 1897. While there he published Folks from Dixiein 1898, The Uncalled in 1898, Lyrics of the Hearthside in 1899, and Poems of Cabin and Field in 1899. Soon after he fell ill and left his clerkship to focus on writing. He then released Lyrics of Love and Laughter in 1903, Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow in 1903, and Howdy, Howdy, Howdy in 1905. He passed away February 9, 1906. Paul Laurence Dunbar will always be one of America’s greatest Black poets.

The African American Museum of Southern Arizona: The African American Museum of Southern Arizona is devoted to gathering and sharing stories, images, and artifacts as they document, digitize, and preserve African American and Black life, culture, and history in Southern Arizona to benefit the community (AAMSAZ, 2022). Their vision is to serve as a resource and to provide the community with an applied and virtual venue and repository for stories, histories, and cultural contributions by African Americans and Blacks in Southern Arizona. Located on the campus of the University of Arizona, they want to improve knowledge of the struggles and triumphs of the African American experience in Southern Arizona and throughout the country. The idea for the museum started when Beverly Elliott, the owner, was helping her grandson with an assignment on an African American hero. He asked if there was a museum in Tucson to learn about African American people that lived here. Elliott looked into it and found that there was not a museum, so her grandson told her that there should be. She agreed, began researching, and has since started the museum. Collections of the museum include/cover the University of Arizona African American Women’s Arch, the Black Cowboys, the Buffalo Soldiers, Tuskegee Airmen, Greg Hansen’s 100 of 2021, and Tucson High Badger Foundation, Inc. Hall of Fame Members. There is information on African American celebrations, how they came to be, and how they are celebrated on their website. Celebrations included are MLK Jr. Day, Black History Month, Juneteenth, 4th of July, National Crown Day, and Kwanzaa. AAMSAZ will have a robust educational program including offering fun hands-on projects for students as they learn about African American and Black history. Students will be able to experience the STEM/STREAM (Science, Technology, Religion, Arts and Math) projects with materials available for a small fee to begin each project during the K-12 student’s visit. Additionally, they support local African American art such as dance, paintings, and sculptures and highlight them. Another way that they are helping to preserve Southern Arizona African American history is through oral history interviews with local African Americans on their experiences and history. Throughout the month of February in honor of Black History Month, they are celebrating and sharing inspiring stories from Southern Arizonans each week. The African American Museum of Southern Arizona is greatly expanding the knowledge of and sharing African American history to the Southern Arizona community and beyond. For more information, be sure to check out their website.

The Arizona Black Rodeo: As you may know, the Tucson Rodeo is hosted in February each year. Local schools even take time off to celebrate the occasion. However, most do not know about the Arizona Black Rodeo. One in four cowboys was Black in the early 1900’s (AAMSAZ, 2022). African American Cowboys may not commonly be seen in Westerns, but they did exist. African Americans and Blacks have been cowboys since the time they were enslaved. The Arizona Black Rodeo is one of the largest and most popular African American cultural and educational events in Arizona. They have attracted as many as 9,000 rodeo fans across a weekend of Western experiences (Arizona Black Rodeo Association, 2021). The mission of Arizona Black Rodeo Association is to “celebrate African American history and culture, and to create memories. We organize an annual rodeo that promotes an appreciation for our cultural heritage, provide education about the role African Americans played in shaping the history of the West while giving youth a hands-on experience with sportsmanship, equestrianism and agriculture” (Arizona Black Rodeo Association, 2021). The Arizona Black Rodeo is important to Arizona and in showcasing the heritage of the Black cowboy. Be sure to check up on when their next events are, and check out their website for more information.

Cow Town Keeylocko: Edward Keeylocko built a western town called Cow Town Keeylocko outside of Tucson, Arizona. When he moved to Arizona in the 1970’s he enrolled in Pima Community College and the University of Arizona to study agriculture. In 1976, he bought about 40 acres of land. His down payment was $1,660 for the $15,800 property, plus interest. He started Keeylocko Land Feed and Cattle Co., and soon there were dozens of cattle, horses and hogs roaming his land (Fifield, 2019). He raised cattle and one day when he went to auction them, no one bought them. He was told that he should build his own town and sell his cows in his own town. He decided that was what he was going to do. He created it by bringing in materials with his pickup truck and built it by hand with a shovel, a digging bar, a shifter board, and a packing device. The town is powered by generators, and there is no hot water, but it is a place that has brought many people together. He wanted to create a space that everyone was welcome. He would refer to Cowtown as the “real wild West.” Ed has since passed away December 25, 2018. The town/ranch is still there today and hosts events regularly. There is also camping available.

The Buffalo Soldiers and Fort Huachuca: The First African American soldiers to arrive in Arizona at Fort Huachuca were the Buffalo Soldiers in the 1890s; the 9th and 10th Cavalries and the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments. All four of the Buffalo Soldier units were stationed at Fort Huachuca at one point in their history. They were former slaves because after the Civil War ended in 1865, 1866 is when Congress authorized the Army to enlist black men in the regular army (Brown, 2018). Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Huachuca in the 1916-18 period, and all the way through the Mexican Revolutionary War period at the same time were the Border Patrol (Brown, 2018). They were sent to Camp Naco, Arizona, Camp Little in Nogales, and others. During the WW II, Fort Huachuca was the home of the only two Black Divisions in the history of the U.S. Army, the 92nd & 93rd Divisions and subsequently the largest concentration of black officers. The larger of the two hospitals was the only black commanded and staffed hospital in the Army (SWABS, 2020). They are an essential part of Arizona history. To learn more, check out the Southwest Association of Buffalo Soldiers here.

Estevan Park: The park is named after the first non-native to travel through the Southwest. Estevan de Dorantes was of African descent and an enslaved man who was the first non-native person to visit the southern Colorado Plateau in Arizona and New Mexico. His formal name "de Dorantes" comes from his status as an enslaved person. He was the property of Andrés Dorantes, a captain of the ill-fated Narváez Expedition of 1527. This entrada of 300 men shipwrecked of the coast of Texas. Only Esteban and three others survived and for the next 8 years they wandered the Southwest US and northwest Mexico (U.S. DOI, 2019). The stories from their journey spread around and rumors of wealthy civilizations started. Some wanted to know if they were true. Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza was one of them and he purchased Estevan from Andrés Dorantes and contracted him to accompany a Franciscan priest, fray Marcos de Niza, to Cíbola (U.S. DOI, 2019). Esteban was sent ahead to see what he could learn about Cíbola from the native people. Estevan throughout his journeys took time to learn from the indigenous communities about their languages and culture. He became the first non-native person to contact the Zuni and others. He had been blocked from entering Cíbola, and it is unsure what happened to him from that point. Learn more about Estevan here.

African American Women Arch: When the University of Arizona was creating their Women’s Plaza of Honor, community members ensured that an arch represented African American Women in Tucson. The arch was dedicated on Sunday February 26, 2012 (AAMSAZ, 2022). It has the names engraved of women who have made outstanding contributions within and outside the Tucson community. Their names are Daisy Jenkins, Dr. Doris Ford, Anna Jolivet, Saundra L. Taylor, Dr. Laura Banks Reed, Lisa Benson, Lillian Brantley Thompson, Wanda Moore, Irene Hutcherson, Carolyn Patterson, Pam Fleming, Ruth W. Brinkley, Delta Sigma Theta – Tucson Alumnae Chapter, Gloria Copeland, Darlene G. Crooms, Gwen Crooms, Lisa Ordonez Crooms, Quincie Bell Davis, Etta Mae Dawson, Beverely Elliott, Dorothy June Parker, Sadie Pitts, Tommie Thompson, Sadie Osborne Turner, and Michelle Williams. Be sure to visit the next time you are on campus.

Works Cited:

Academy of American Poets. (n.d.). Paul Laurence Dunbar. Poets.org. Retrieved February 21, 2022, from here.

African American Museum of Southern Arizona (AAMSAZ). (2022). Welcome to the African American Museum of Southern Arizona. African American Museum. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from here.

Arizona Black Rodeo Association. (2021). Arizona Black Rodeo: The hottest show on dirt! AZ Black Rodeo 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2022, from here.

Brown, A. (2018). Black History In Southern Arizona. YouTube. Arizona Public Media. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from here.

Dark Rye. (2013). Cowtown Keeylocko. YouTube. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

The Dunbar Pavilion. (n.d.). Retrieved February 10, 2022, from here.

Elliott, B. (2022, February 2). The African American Museum of Southern Arizona. Yurview. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from here.

Fifield, J. (2019, March 14). Rancher built Tiny Town on a dream. what happens now that he's gone? The Arizona Republic. Retrieved February 24, 2022, from here.

Glogoff, S. (2005). Dunbar School: Shared Memories of a special past. DUNBAR SCHOOL: Shared Memories of a Special Past | Through Our Parents' Eyes. Retrieved February 17, 2022, from here.

Poetry Foundation. (2022). Paul Laurence Dunbar. Poetry Foundation. Retrieved February 21, 2022, from here.

Southwest Association of Buffalo Soldiers (SWABS). (2020). Southwest Association of Buffalo Soldiers: Tribute to Buffalo Soldiers. Southwest Association of Buffalo Soldiers. Retrieved February 24, 2022, from here.

U.S. Department of the Interior. (2019, June 28). Esteban de Dorantes. National Parks Service. Retrieved February 24, 2022, from here.

Comments